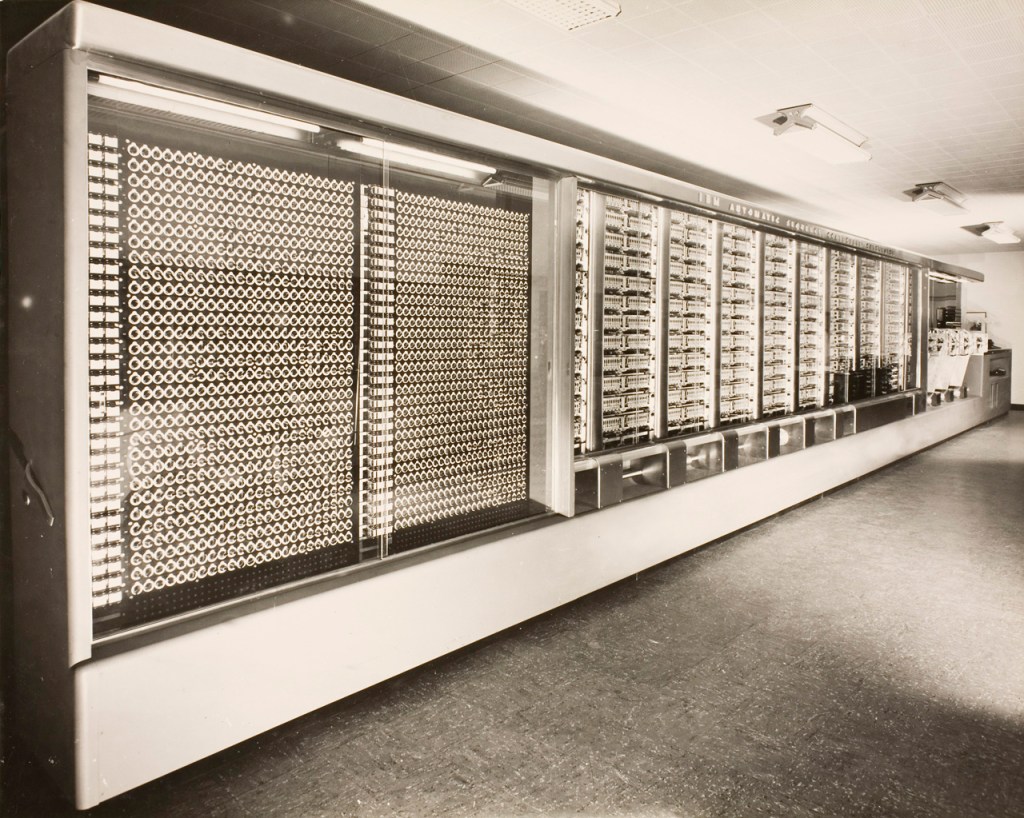

Electro-mechanical computers were a fascinating step in the evolution of computing technology. These machines emerged in the early-to-mid 20th century and used both electrical and mechanical components to perform calculations. They relied on relays and switches to process data, unlike purely mechanical devices that preceded them.

One of the most notable examples was the Harvard Mark I, developed in the 1940s. It was used for complex mathematical computations, including assisting in World War II efforts. Although relatively slow by today’s standards, these computers laid the groundwork for fully electronic computers by demonstrating the feasibility of automated computation.

These computers had very little scope of input and output information flow which it was based primarily in rotary buttons and lights indicators. Electro-mechanical computers were programmed using punch cards or physical switches, rather than modern programming languages. The instructions were essentially hardwired or fed into the machine via punched paper tape or cards, with each hole representing a specific command or data input.

For example, the Harvard Mark I used a system of punched tape to store instructions, and it operated based on a sequential execution model—meaning each command was executed in order, with no branching or conditional logic like in modern programming. Early programs were often written in numerical codes that corresponded to specific machine operations.

Programming these machines was a meticulous and manual process, requiring careful planning to ensure efficiency and accuracy. It laid the foundation for later developments in assembly languages and high-level programming.